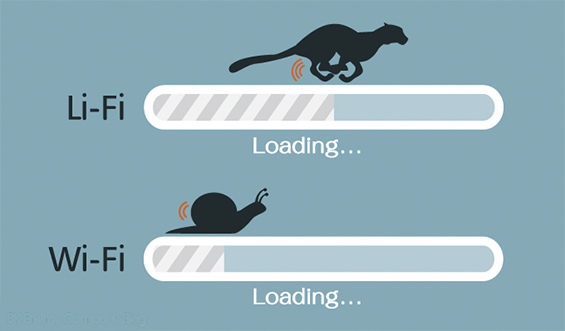

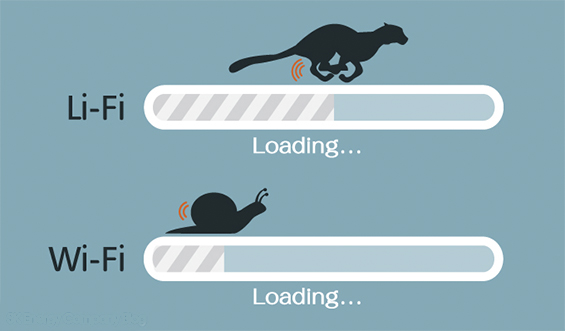

Li-Fi, a new, super-fast alternative networking technology capable of reaching speeds hundreds of times faster than current standards in real-world use, could soon replace Wi-Fi.

Harald Haas, a professor of mobile communications at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, has created a working model of a Li-Fi system, transmitting data through LED lightbulbs flickering on and off over a matter of nanoseconds. Haas recently demonstrated his prototype by transmitting a video from an LED lamp to a solar cell on a laptop.

“Li-Fi is essentially the same as Wi-Fi, except for a small difference—we use LED lights around us to transmit the data wirelessly as opposed to using radio,” Haas says.

Wi-Fi, which currently carries half of the world’s internet transmissions, works by using radio signals to transmit data to a number of electronic devices, including phones and laptops. As more people gain access to the internet, the use of Wi-Fi is expected to expand, which experts such as Haas believe will result in the creation of a “spectrum crunch” that would see Wi-Fi networks slow down under the high demands, reports Adam Boult for The Telegraph.

“Radio spectrum is not sufficient,” Haas says. “It’s heavily used, it’s very crowded…we see that when we go to airports and hotels, where many people want to access the mobile internet and it’s terribly slow. I saw this coming 12, 15 years ago, so I thought ‘what are better ways of transmitting data wirelessly?’”

Li-Fi was found to reach speeds of 224 gigabits per second in a lab setting, which could allow a person to download 20 full-length movies in just one second. Haas’s research shows Li-Fi can achieve data density 1,000 times greater than Wi-Fi because Li-Fi signals are limited to a smaller area.

In addition, whereas Wi-Fi can extend through walls, allowing neighbors to “share” the connection, Li-Fi is not capable of this, and can be contained by closing the curtains, which could make it potentially more secure.

Haas went on to say that lights would not need to be kept on throughout the house in order for the system to work. The bulbs could be dimmed to a level in which they appear to be off but are still transmitting data, writes Emily Matchar for The Smithsonian.

The technology also has possibilities for smart home appliances by creating a network for devices located within a home to talk to each other.

One company, Velmenni, recently put the technology into real-world situations in offices and industrial environments in Estonia, finding that it was capable of reaching the high speeds attained in the lab.

Several other companies, including Oledcomm and pureLiFi, have also jumped on board to bring the technology to customers. Both companies offer a kit to aid in the installation of Li-Fi networks at home and in the office, with pureLiFi promising speeds of 10 Mbps.