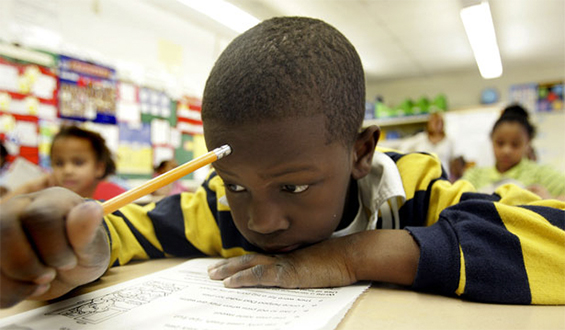

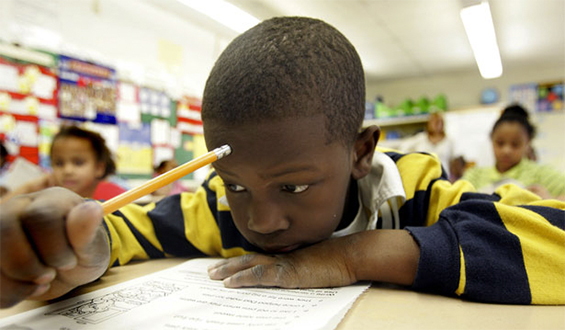

Recent studies show that schools may be doling out harsher punishments for minority students – and the issue seems to start at a very early age. While suspension and expulsion are both widely-accepted means of dealing with kids who misbehave, research shows that it can often lead to them ending up in prison instead of college.

Melinda D. Anderson of National Journal recently asked the question, “Why are so many preschoolers being suspended?” In that article, Anderson tells of Tunette Powell, who travels all over the country mentoring the youth and counseling their families. Her children’s preschool sent home her three and four-year-old boys eight different times in one school year.

Powell wrote an opinion piece for the Washington Post in which she stated:

“So many parents reached out [to me]… a lot of black mothers… We live in a time when we just say, ‘Suspend them, get rid of them.’”

While the issues start with preschool minorities, it goes beyond three and four-year-olds. Just last week, The Seattle Times featured a piece by John Higgins which revealed data on the number of times students in the Washington area were expelled or suspended, how long they were suspended or expelled for, and why they are sent home. These numbers, posted on the Office of Public Instruction website, track the students by many factors, including race.

According to the report, both in Washington and in the entire country, schools tend to suspend African American students “at rates that far exceed their overall enrollment.” The article explains that, “In the 2014-2015 school year, for example, about 10 percent of the 44,655 kids removed from Washington classrooms were African-American, but they make up less than 5 percent of all students.”

San Bernardino County also seems to be suffering from an epidemic of minority student mistreatment. In an article from The Center for Public Integrity, Susan Ferriss shares:

“Josue “Josh” Muniz, now 20, is suing the San Bernardino City Unified School District and a school police officer for excessive force and negligent training. The suit alleges that the officer grabbed Muniz, then 17, by the throat, pepper sprayed him and beat him before arresting Muniz for assault on the cop. Muniz says the officer was upset because he and girlfriend hugged after he ordered them to separate. The charge was dropped in court.”

Muniz admits to hugging his girlfriend during their lunch break, and also agrees that the cop asked them to separate. He says that although he did move away from his girlfriend when ordered to do so, he moved back to hug her again, “because she was upset.” That’s when the cop allegedly grabbed Muniz by his throat. He pushed the policeman to get him “just a little bit off me,” and as the two stumbled to the ground, the cop squirted pepper spray in Muniz’s face. The 17-year-old found himself facing charges of misdemeanor assault on a police officer.

Muniz is not alone. There were tens of thousands of juveniles arrested by the school’s police officers in San Bernardino County over the last ten years.

Ferriss explains:

“Based on 2011-2012 data collected from U.S. schools by the U.S. Department of Education, the latest available, Muniz’s Arroyo Valley High referred students to law enforcement at a rate of 65 for every 1,000 students. That was more than 10 times the national and California state rate of 6 per 1,000.”

Those numbers raised red flags for critics all across the nation who have accused school districts and police of flooding the “school-to-prison pipeline” with minority students and taking away their chances at having a normal life.