The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has announced that doctors should work together with school administrators to develop individualized action plans for treatment of students with epilepsy who have prolonged seizures, says Molly Walker, writing for Med Page Today.

In its first clinical report on the topic, the AAP said that the action plans should contain the medication the child will need, who will be responsible for giving the child the medication, and when and how to seek additional emergency medical care. The report’s authors were Adam L. Hartman, MD, and Cynthia Di Laura Devore, MD, of the AAP’s Section on Neurology and Council on School Health, who published in the journal Pediatrics.

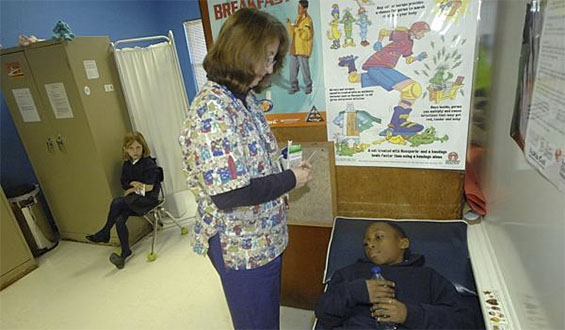

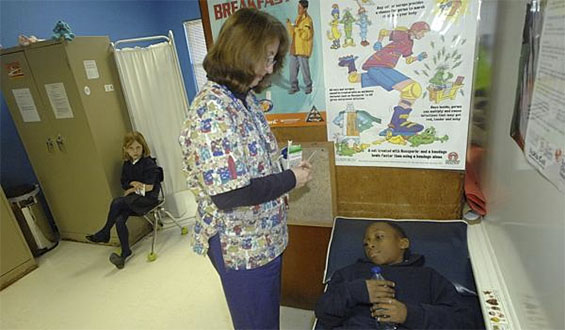

It is possible that principals and other providers will have to step in to administer the rescue medication if there are issues that prevent the school nurse from being able to do so. It may be necessary that other assisting personnel will require additional training.

Dr. Hartman explained that the main purpose of this report was to make pediatricians and neurologists aware of the legal and logistical issues involved in creating individualized seizure action plans for a school setting.

“Not all schools have nursing staff readily available in the school building, let alone in the school transportation or school activity settings,” he wrote in an e-mail to MedPage Today. “Legal liability for medical treatment also may vary between jurisdictions. Therefore, these seizure action plans are important so that students can participate safely in whatever programming the schools have to offer.”

The administration of the seizure rescue medication may be the essential part of the action plan. Although there are several medication options for students with epilepsy, the authors recommend medicines that are given bucally (orally) or through the nasal passage because they are the least restrictive choices.

Even these drugs have restrictions, however. If midazolam and lorazepam are administered bucally, the patient must not have profuse secretions or vomiting during the seizure. A crushed clonazepam tablet may be used, but special training could be required to avoid injury from the clenched teeth of the patient while administering the medication.

Another new route of administration is intranasally by using a premeasured syringe. This method would also require the provider to have additional training since this procedure is “relatively new.” Rectal diazepam gel is widely used for seizure rescue but requires the patient to be partially undressed. If the school nurse is unavailable, others could find administration of this method uncomfortable.

Additionally, providers must counsel school officials on any potential adverse effects of the medication and how to address them if they occur. Guidance must also be given regarding the logistics of a prolonged seizure, when to ask for medical advice, and concerns about any other complications.

Lara C. Pullen, Ph.D., writing for Medscape, shares a quote from Dr. Devore:

“This paper is an effort to assist pediatricians, and possibly school districts, in designing advance planning to secure the safety of children and adolescents with epilepsy so they can participate in virtually all school activities to their full potential in a safe fashion.”

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and the Rehabilitation Act have been around for many years now, but there is still a lack of regularity of practices and laws among states and school districts. An example is that not every school has a school nurse who can perform the medical plans from a specified “clinic.”